The Doge of Los Angeles Jennifer Kim

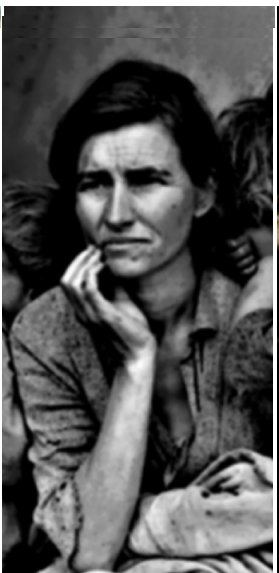

Margaret Leslie

Davis is a graduate of Georgetown University. Davis is also a California lawyer and author. She has also written Dark Side of Fortune:

Triumph and Scandal in the Life of Oil Tycoon Edward L. Doheny and Rivers in the Desert: William Mulholland and the

Inventing of Los Angeles for

which she won the Golden Spur Award for Best Non-Fiction Book by the Western

Writers of America. She currently resides in Los Angeles, California.

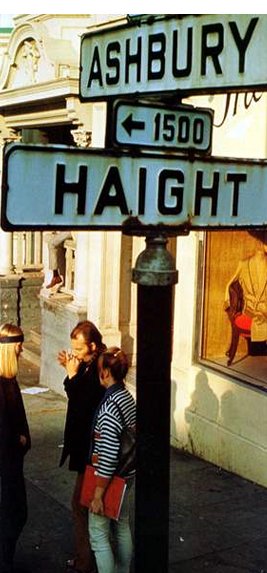

Dubbed as the ¡§Doge of Los

Angeles¡¨ by one historian, Franklin D. Murphy played a powerful role at the

heart of virtually every new cultural institution in the city. 1

Margaret Leslie Davis delivers the compelling story of how Murphy influenced

academia, the media, and cultural foundations to reshape a ¡§cultural backwater

to a vibrant center for the arts.¡¨2 For approximately three decades,

Murphy helped shape the city of Los Angeles into a world-class

metropolis using his relationships with founders of some of America¡¦s greatest fortunes. By

channeling more than one billion dollars into the city¡¦s arts and educational

foundation, Murphy advanced Los Angeles into a brilliant

world-classed city ready for its role in the new period of global trade and

cross-cultural arts.

Born

on January 29, 1916 in Kansas City, Missouri, into a family that valued

rational thought, young Franklin Murphy was energetic and adventurous. He grew

up reading his ¡§way to exploits¡¨ with the novels of Sir Walter Scott and the Tom

Swift series for boys, hardly imagining that as an adult he would

¡§encounter a social and intellectual revolution.¡¨3 Murphy first

attended Kansas University, and then he was accepted

into the University of Pennsylvania, School of Medicine, his father¡¦s alma mater.

However, Franklin delayed this entry for a

year to attend the University of Göttingen in Germany where his father also had

studied. He chose to delay his admittance into University of Pennsylvania because he wanted to follow

his father¡¦s footsteps ¡V allowing ¡§two Franklin Murphys to have worked in the

same laboratories of the same German university.¡¨4 After he

graduated from the University of Pennsylvania, Murphy was promised a

teaching position at its medical school, but returned instead to the medical

school at the University of Kansas in hopes of improving the

institution. Murphy was then asked by the regents of the University of Kansas to accept the

chancellorship. After accepting and serving as chancellor at the University of Kansas, Murphy was given the

opportunity to be the chancellor at the University of California in Los Angeles. Before arriving in Los

Angeles, Franklin Murphy had read about the idiosyncrasies of the city and its

reputation as a ¡§cultural wasteland,¡¨ but to his surprise, he found

the city curiously exciting.5 Franklin Murphy was welcomed into the

circle of three strong-willed Los Angeles regents: Edward W. Carter, a

¡§charismatic and powerful retail-chain tycoon¡¨; Edwin Wendell Pauley, a

¡§steadfastly conservative oil millionaire¡¨; and Dorothy Buffum Chandler, an

¡§obsessive doyenne, a driving force in the family that owned the Times Mirror

company and the Los Angeles Times.¡¨6 In November of 1961,

Edward Carter nominated Murphy to be the chairman of the county art museum¡¦s

building fund campaign. His new role gained him recognition in the community.

To Murphy, the art museum was another symbol of ¡§coming cultural matur[ation]¡¨

of Los Angeles.7 The Los Angeles County Museum of Art then

opened in the spring of 1965, following the opening of another arts

institution, the Los Angeles Music Center on December 6, 1964. Not long after the opening of the two institutions,

Ronald Reagan announced his candidacy for governor of California on January 4, 1966. However, Reagan¡¦s campaign rhetoric was deeply

disturbing to Murphy. For two years Murphy underwent severe funding cuts

ordered by the governor. Then, on February 17,

1968,

Murphy officially resigned from his position of chancellor and took the

position of chief executive officer at Times Mirror.

Franklin

Murphy arrived in September 1968 to take up his duties at Times Mirror. The

fact that a chancellor was selected to serve as a chairman and chief executive

stunned many company officials. Furthermore, Murphy had never run a business,

nor did he have experience managing a corporate enterprise of such size. Murphy

underwent a transformation as he eased into a powerful role¡Xthe former

university chancellor operated at the same level of power and prestige as many

major businessmen who previously had been targets of his fund-raising. His

world rapidly expanded as he was asked to join numerous civic organizations and

corporate boards. Increasingly, leading figures in business, government,

entertainment media, and the arts sought chances to become better acquainted

with the new chairman. The Times Mirror Company gradually became a

¡§communications force responsible for leadership¡¨ as reporters

working under Times covered and wrote articles pertaining to the intense

1968 presidential campaign.8 Subsequently in 1976, Times Mirror

achieved its best year and stood on the threshold of becoming a billion-dollar

enterprise. In spite of this, Times Mirror did falter when it, along with other

publishing enterprises, tried to purchase urban newspapers, chains, and

independents in order to increase profits and promote growth. Although Times

Mirror lost several choice properties, industry observers ranked it the

country¡¦s ¡§most profitable publicly held publishing company.¡¨9

In

1970, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art board persuaded Murphy to accept the

difficult role of museum president. Murphy was most concerned that the museum

was an ¡§art museum without art.¡¨10 Franklin Murphy had a solution in

mind¡Xto obtain the prized Norton Simon Collection, which had a market value of

150 million dollars. Ownership of Simon¡¦s collection, he believed, would be a

magnet for future donations. However, Norton Simon demanded that Murphy meet

his requirements before negotiations began about his collection. The board and

the museum staff hurried to meet Simon¡¦s demands, but he was never satisfied.

In spring of 1971, Simon stunned museum trustees with the announcement that he

planned to sell more than seventy paintings and sculptures at an auction¡Xmost

of which were already on loan to the museum. Murphy recognized that hope of

obtaining Norton Simon¡¦s collection was dwindling. In 1971, Armand Hammer, an

oil tycoon, boldly announced his plan to donate more than ten million dollars

worth in paintings, including a world-famous Van Gogh piece to the Los Angeles County Museum. As his term as museum

president was coming to a close, Murphy focused his energies on the museum¡¦s

future. However, the museum suffered a ten percent cut in funds from the county

after the passage of Proposition 13 in 1978¡Xa ¡§$284,000 loss to the annual

operating budget.¡¨11 Moreover, by 1985, Franklin Murphy had served

for twenty-one years as a trustee of the National Gallery, a renowned

institution founded by Andrew Mellon. As a chairman of the National Gallery,

Murphy¡¦s best asset was its director, J. Carter Brown, who brought new

enthusiasm and a fresh approach to his duties as director. Brown, like Murphy,

was dedicated in making art accessible to a wide audience. When selecting works

for exhibitions he arranged, referred to as blockbusters, Brown was

far-ranging, in that he felt no need to confine the National Gallery¡¦s space

with only old masters and familiar American works. In addition, Murphy thought

of the National Gallery as ¡§America¡¦s finest example of the mix of public and

private resources,¡¨ a partnership between the federal government and the

American people.12 Murphy¡¦s reputation for clear thinking when in

chaos was repeatedly tested in his performance on the various restless boards

on which he served. Murphy¡¦s negotiations with Armand Hammer and Norton Simon

took much of his prime years of his life, but he was left without the prizes he

sought after. Despite the failure, Murphy was recognized as a prodigy in a

world of trusteeship.

Franklin Murphy, Ed Carter,

and Dorothy Chandler had formed an effective team as culture builders. The ¡§old

guard¡¨ was being replaced by forceful corporate leaders whose fortunes were not

from traditional sources like oil or land sales, but from financial services,

entertainment, technology, and global trade.13 Murphy¡¦s authority in

Los Angeles was still extensive, and though his influence rarely came to the

attention of the general public, it was well known in corporate and academic

circles. Murphy continued to make a notable difference in Los Angeles through the sponsorship of

the Ahmanson Foundation, in which he was a trustee. The Ahmanson Foundation was

found by Howard Ahmanson, a key figure in the power structure of Los Angeles. The foundation

administered funds for the ¡§public welfare and for no other purpose.¡¨14

Murphy wanted each dollar of the millions that were donated to the community to

serve as a way to activate constructive energies. When the foundation was in

jeopardy with conflicting reports about the foundation¡¦s assets, Murphy

protected the enormous financial assets of the foundation, and also guided the

institution to a sense of purpose and humanistic goals. By guiding the

overwhelmed institution through its most unstable time Murphy¡¦s greatest gift

to Los Angeles gave was his stewardship of

the Ahmanson Foundation. By the

1990s, the foundation was contributing nearly 20 million dollars each year in

local grants. Murphy took pleasure in the times he arrived on the scene to save

an endangered city institution. One such rescue came when KCET, the city¡¦s only

public television station, could not meet its monthly payroll and was forced to

put its Hollywood studio up for sale. Vital Ahmanson Foundation support

allowed for the station to continue for many years. Franklin Murphy, then,

reached the mandatory age of retirement, seventy-five, in 1991. He had mastered

the art of trusteeship during an exceptional period in Los Angeles when enthusiasm for

cultural development allowed him to apply his managerial and scholarly talents.

Perhaps the most emotional event for Murphy¡Xthe ¡§realization of twenty-nine

years of promise and planning¡¨¡Xwas the long-awaited opening of the UCLA Fowler

Museum of Cultural History.15 As a chancellor in the 1960s, when

sensitivity to world cultures was drawing the attention of scholars and

activist students, Murphy envisioned the launch of the museum to fill an

obvious gap in the study of cultural history in non-Western traditions. Then in

the fall of 1993, Murphy was diagnosed with acute cancer of the mouth and jaw.

Even with his health deteriorating, Murphy continued to take pleasure in

dispensing grants as a trustee of the Ahmanson Foundation. Soon, his cancer

spread to his lungs and Murphy died in his hospital bed at the UCLA Medical Center on June 16, 1994. His legacy and memory continues in the institutions

he fostered. His desire to see cultural centers as a ¡§home for the humanities¡¨

merged with his belief that building steadily on cultural awareness was part of

the ¡§path to civic harmony.¡¨16

Through

her book, Margaret L. Davis introduces a man who is hardly known, but has

helped develop one of the largest cities and counties today. Davis praises Franklin Murphy for

his contributions to the city of Los Angeles and his enormous managerial

ability to advance Los Angeles into a cultural and

artistic crossroads. Davis believes Murphy was a man who has done more to

¡§shape the cosmopolitan cultural image¡¨ of Los Angeles than any other person of

his generation.17 However, Davis¡¦s focus is not only Murphy, but

also on the growth of Los Angeles as a cultural center with Murphy playing an

integral part in transforming the city into a modern metropolis. From a

¡§cultural backwater¡¨ to a ¡§vibrant center¡¨ for the arts, Murphy transformed the

city by opening two of California¡¦s largest and most well-known

museums ¡V the Los Angeles Museum of Art and the National Gallery, and

developing the University of California system. Murphy¡¦s array of

positions and roles allowed him to influence the worlds of not only artistic

institutions, but extend also to academia and journalism.

Davis seems to forgive Murphy for

many of his faults, such as his bad temper, which he often took out on his

employees. It also seems she glosses over his extra-marital affairs, giving few

hints of the passion or angst of Murphy¡¦s personal life. The ease with which

she dismisses them leaves the reader wondering what other parts of Murphy¡¦s

life may also be omitted. Also, Davis¡¦s work suffers from her ¡§inattention to

the other type of culture inherent to Los Angeles¡¨, for instance, the film

industry; instead, Davis keeps her focus on fine arts, good books, and

classical music.18 Davis explains the dealings of the urban elite as

they negotiated the world of high art, but ignores the film industry which also

shaped the metropolis. Margaret L. Davis also views Franklin Murphy detachedly,

telling of his intellectual skill with subtle separation from his wealthy

contemporaries. Davis writes in the tone similar

to diplomatic historiography because she sounds like a realist¡Xdiscussing a

person who cultivated a city into its vibrant self today.

In

Emily E. Straus¡¦s review of Margaret L. Davis¡¦s book, Straus deems that Davis¡¦s book will be of interest

to urban historians, especially those who ¡§study how decisions are made in

cities¡¨ and how ¡§individuals can help shape these decisions.¡¨19

Straus states that Davis not only tells the history of Murphy, but also offers

insight into the histories of such disparate subjects such as Dorothy Chandler,

the Ford Motor Company, the Nixon presidency, and UCLA. By doing so, she shows

the interconnectedness of the media, the arts, politics, business, and

academia, while illustrating how personal relationships and connections play

central roles in the workings. Straus also mentions that by

understanding the bonds made through the personal relationships one will fully

understand Murphy¡¦s position of being a culture broker, a middleman emphasizing

commercial aspects and facilitating the crossing of one group from one culture

into another.

In another review, Jim Newton,

an editor from the Los Angeles Times, states that Davis¡¦s examination of Los Angeles through the lives of its

civic and cultural leaders is a ¡§significant, if imperfect, contribution.¡¨20

Newton believes Davis¡¦s work supplies the

residents of Los Angeles with an understanding of

themselves and simultaneously, delivers subtle messages for today¡¦s leaders. To

Newton, not only is the Culture Broker a book about the formation of Los

Angeles, but also a jolting reminder of how much the city¡¦s cultural and

corporate leadership has changed from the days of Murphy¡¦s dominance. Newton believes Margaret L.

Davis¡¦s book is useful not only in presenting how Murphy led Los Angeles, but also in introducing a

standard for today¡¦s leaders to meet.

Davis provides deep insight into

the transformation of Los Angeles and the lives of the people

who had major influences on the development of the city into a cultural focal

point. To have gone through ¡§extensive research, papers, numerous oral history

interviews¡¨, Davis surely conquered a ¡§large task.¡¨21 Davis presents a book about a man

who dedicated more than half his life into advancing the city of Los Angeles. Through him, the University of California system has been influenced

so that, for example, UCLA and UC Berkeley are on par financially. By reading

her book, readers will be able to appreciate the works of Franklin Murphy and

be able to understand how long and how much effort it takes for a city to

mature.

But

today, Franklin Murphy is still a not well known person. However, Franklin

Murphy deserves to be recognized by all throughout California for his undying

determination and dedication of evolving Los Angeles¡¦s cultural and artistic

scene; also for guiding Los Angeles through an ¡§era of radical change that

rejected the creed of the modern.¡¨22 With the help of others, Murphy

was able to bring vibrancy to a city that was once dull and superficial. By

introducing the appreciation of art, culture, and music by ways of museums and

music halls, the city of Los Angeles diversified in its

appreciation of the arts.

1. Kurzman, Dan. Disaster! The Great San

Francisco Earthquake and Fire of 1906. New

York: HarperCollins 1. Davis, Margaret Leslie. The

Culture Broker: Franklin D. Murphy and the transformation of Los

Angeles. Berkeley:

University of California

Press, 2007. xi.

2. Davis,

Margaret Leslie xi.

3. Davis, Margaret Leslie 1.

4. Davis, Margaret Leslie 4.

5. Davis, Margaret Leslie 25.

6. Davis, Margaret Leslie 27-28.

7. Davis, Margaret Leslie 55.

8. Davis, Margaret Leslie 130.

9. Davis, Margaret Leslie 174.

10. Davis, Margaret Leslie 210.

11. Davis, Margaret Leslie 230.

12. Davis, Margaret Leslie 244.

13. Davis, Margaret Leslie 355.

14. Davis, Margaret Leslie 112.

15. Davis, Margaret Leslie 347.

16. Davis, Margaret Leslie 389.

17. Davis, Margaret Leslie 393.

18. Straus, Emily E. Review of the Culture Broker: Franklin

D. Murphy and the Transformation of Los Angeles,

by Margaret Leslie Davis. H-Urban, H-Net Reviews Feb. 2008. 31 May 2008

<http://www.h-net.msu.edu/reviews/showrev.cgi?path=38351204047140>.

19. Straus, Emily E.

20. Newton, Jim.

"Prince of the City." Los Angeles

Times 2008. 28 May 2008

<http://articles.latimes.com/2007/09/23/features/bk-newton23>.

21. Straus, Emily E.

22. Davis, Margaret Leslie 392.